Unreal Part 1 : Architecture + Convergence [DXY Journal]

DesignXY Ltd Journal, looking in depth at how our architectural practice uses digital technologies to visualise projects to high standards, using software that is increasingly shared with the film and game industry [Part 1/4].

[8min Reading Time]

At the end of my diploma course (RIBA Part II), in 2003/04, I was in the process of writing my dissertation, considering the advancement of architecture and construction technology. My central thesis was that technologies that are currently separate, would converge in the near future.

My research investigated how technologies that were being used in other creative disciplines, were often demonstrably being utilised to far greater impact than in the architectural profession. I also hypothesised that the rise of the internet would change the way that we work and how we live, citing the death of the video store as being highly likely - within a decade, that’s exactly what happened.

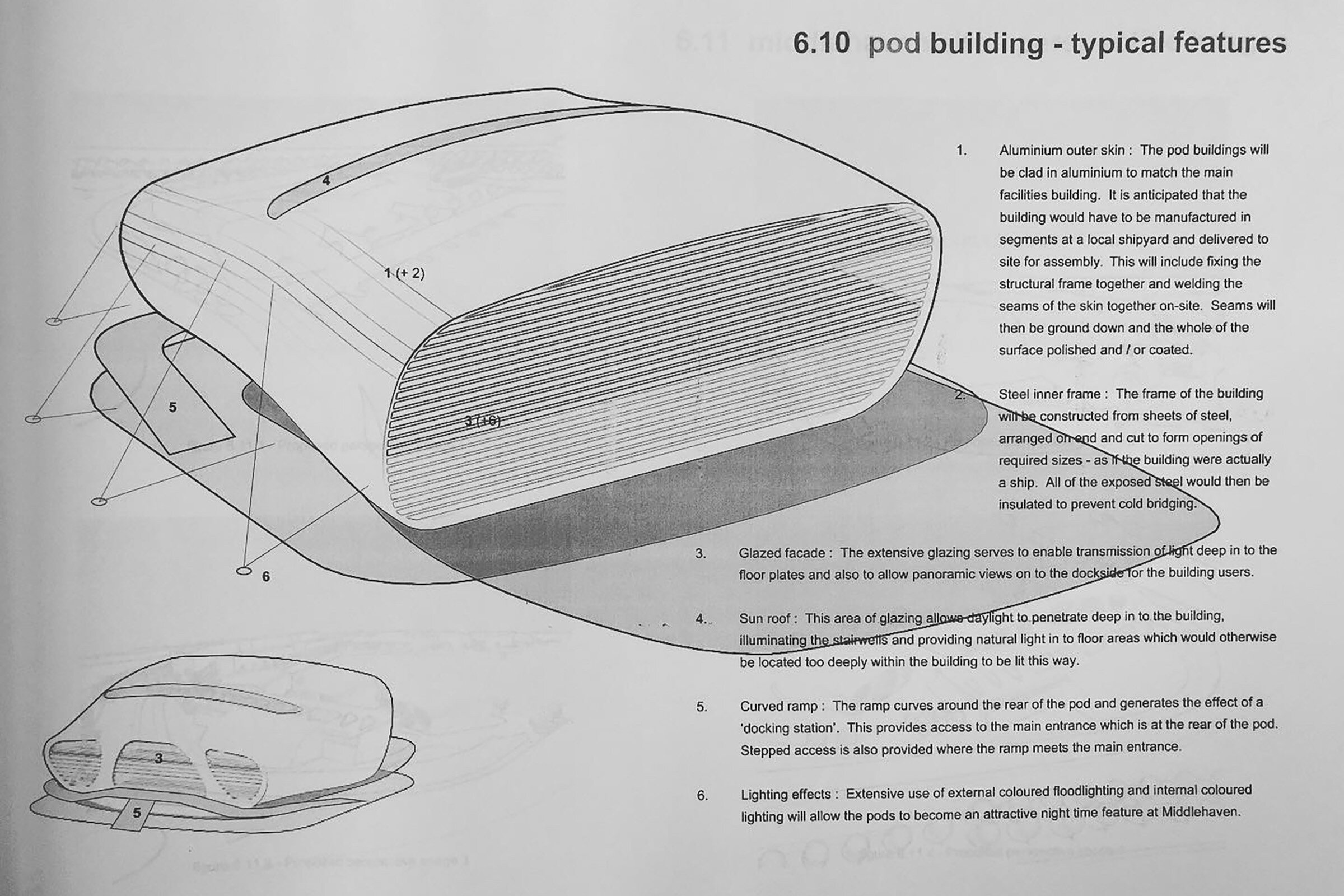

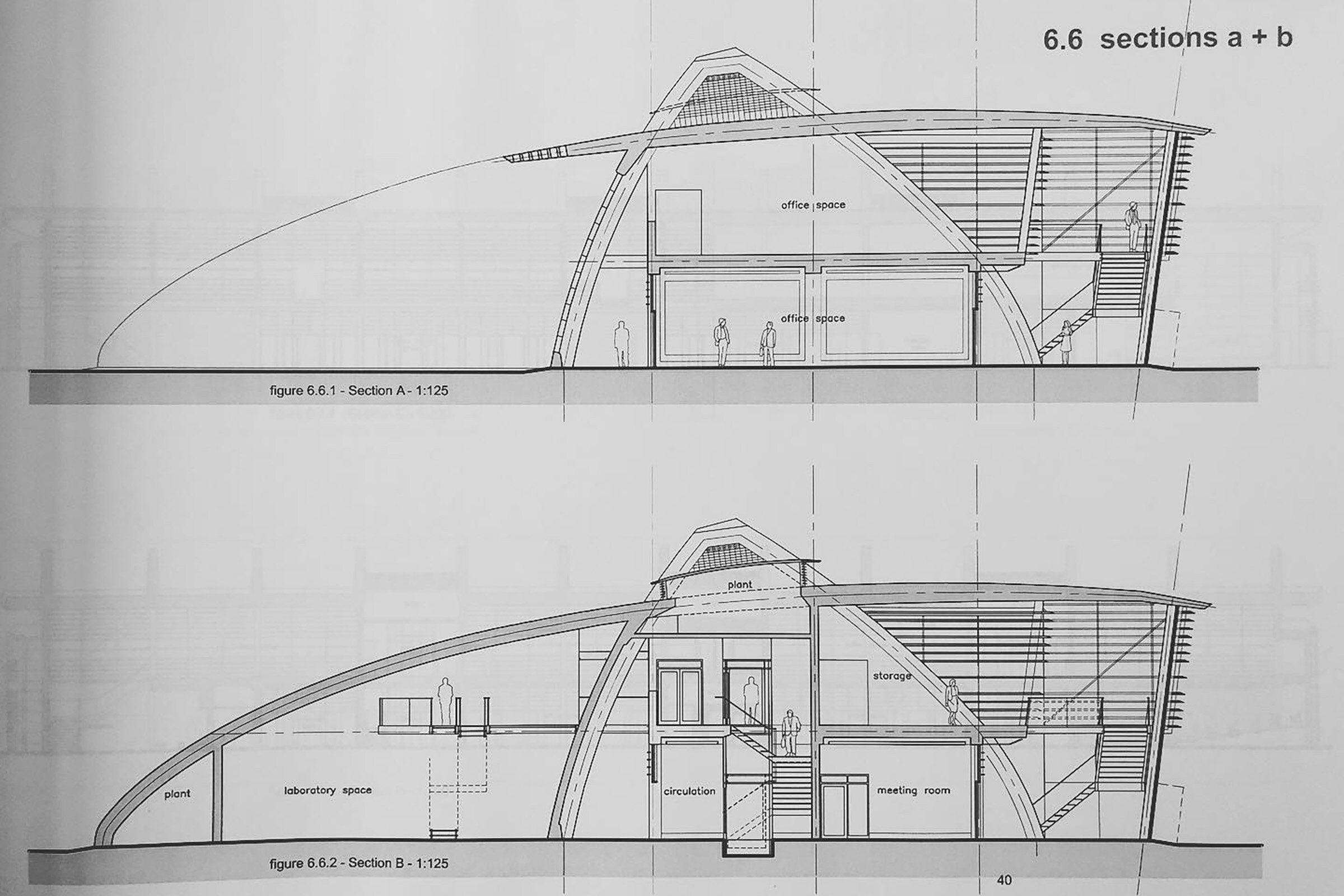

My final design project was based at Middlehaven Docks in Middlesbrough; my building concept was the Architectural Institute for Research, or AIR. The building itself was devised to be a centre for the advancement of the knowledge of construction technology, investigating how information in a digital state can be embedded in physical form.

I drew from many influences in my final design, but science-fiction was and continues to be a source of inspiration and motivation to question what is and what could be. In bringing the impossible to life, the film industry is a prime example of where technology that can be used to showcase building design in the real world, is arguably deployed more effectively by film studios than the vast majority of architectural practices.

The cover of Kris’ RIBA Part II dissertation.

Concept generators of dynamism and stasis.

The form of the Pod buildings, taking design cues from high performance cars and aircraft.

A section through the research building, showing the ‘wing’ profile of the combined roof and walls.

The elevations of the main research building.

A plan view of the main research building.

It’s certainly challenging in terms of which discipline wields the greater creative freedom and influence through their respective take on world building. There are good reasons for that - the primary factor being that films that include vast budgets for design and visual effects, are optimised to yield a high return on investment – the film studio invests money into a production team, which produces a product, which in turn people around the world then pay to see – the aim is often spectacle, rather than reality.

The equivalent architectural analogy would be that a client invests in a design team, which procures a building to which the end-users then benefit. Although architecture in the public realm impacts people, communities and spaces around the respective buildings, the reality is that the budget of relatively few building projects, would directly compare to the budget of a major motion picture. The paradigm is also different; film as a medium is primarily intended to entertain, whereas the purpose of a building is to facilitate a specific use, or range of uses.

Buildings rarely reward spectacle where that comes at the cost of substance; real buildings need to work hard for us, whereas buildings in films just need to facilitate the narrative. On that basis, a direct comparison may not be fair, but the intrinsic link remains. The medium of film uses actual buildings, or draws influence from towns, cities or civilisations of the real world; in turn, architecture draws influence from the potential visions of what could be, as seen on the silver screen.

The question at the heart of my thesis has continued to develop as my career has progressed. Architects are creative professionals; why then, is the industry so inconsistent in using the full range of the tools available to us, to portray the various iterations of our building designs in the best possible light?

I think many architectural practitioners will cite the need to maintain competitive fee levels as the primary restriction. While I understand this, it is perhaps short-sighted, especially for the practices with ambitions to work on larger scale projects in the future. Other practitioners will claim that for many years, the process of visualising a project necessitated that two different 3D models would be created – the first would be the working model, from which all of the construction information was developed and maintained, and the second model, which was entirely separate and used solely for rendering purposes, requiring the time for both models to be maintained independently.

It’s costly enough to have to develop the 3D model for the core architectural purposes, never mind something that’s purely for visualisation. The cost of time; the cost of software; the cost of employing specialists – all are barriers to deploying the technology that can showcase our architecture as we should want it to be seen. The cost of avoiding all of these things, is that we see other industries doing the presentation aspects of our job, better than we do it ourselves. It could be argued that other industries have a wider impact on the public perception of architecture, when compared to practicing architects.

High Rise (2015) - Ben Wheatley’s dystopian vision of vertical segregation.

High Rise (2015) - Opting to use many physical sets, the CGI used in the film was mainly in external shots.

High Rise (2015) - Light and pastel colours serve to soften and contrast with the hard concrete surfaces.

Film and games as media were hugely influential in my formative years and remain an important source of inspiration in my life, in challenging my aspirations as a designer and motivating me to push forward in architecture.

There are many titles that deserve a mention, in terms of the impact that they’ve had on my thinking over the years, but in this Journal series, I want to orbit around the technology that has manifestly converged three of the most important creative disciplines in contemporary culture; film, games and architecture.

For many years, Autodesk as a developer of software, has been a major influence on designers in many industries. I have personally used Autodesk software since 1994, beginning with a version of AutoCAD running in DOS, prior to the release of Windows 95. Since then, I’ve used various versions of AutoCAD, Architectural Desktop, 3DStudio Viz, 3DStudio Max, Revit and Revit LT. I also used ArchiCAD by Graphisoft for around three years, as well as Cinema4D.

My observation from the economic crash in 2008/9, was that fewer people were using the software, so the costs went up, seemingly taxing the companies that somehow found ways to operate despite the tough circumstances. Schemes that allowed companies to own their software outright, often with subscriptions for annual upgrades, were replaced by wholly subscription based models; effectively renting the software at increasing costs per annum.

It’s no secret that many practice runners were left questioning the pros / cons of continuing to use their practices’ design software – the industry is therefore entirely ripe for disruption, in the form of a software developer that distributes their product to designers via a different cost model; perhaps it’s possible to monetise the product by means other than direct sales?

With the worldwide impact of Covid-19, this situation will only be compounded further. My practice has received a deluge of speculative applications to join us, from potential new team members – that’s somewhat normal during the late Spring and Summer, as architectural students seek work placements, but the applications from recently practicing architectural staff clearly demonstrate that highly qualified people have lost their jobs; practices are having to make very hard decisions, forced by the economics of operating in a pandemic, where the focus for so many has shifted to simplification and survival.

All of this leaves me asking two questions. How can DesignXY continue to improve the services that we offer to our clients? How can we do that and remain competitive with our fee levels?

Control (2019) - Set in a spectacularly Brutalist form, much of the pleasure in this game is derived through taking in the architecture.

Control (2019) - Interplay between repeating forms serves to create a familiarity in the environment, which can be easily changed with lighting.

Control (2019) - The addition of carpet and the introduction of tactile timber elements, serve to soften the otherwise cold and unforgiving concrete structure.

Black Panther (2018) - Stripping away the textures, lighting and other computer generated effects, we can start to see the constituent elements of the 3D models.

Black Panther (2018) - The computer model behind the Wakandan night scene.

Black Panther (2018) - The fringes of a city that’s entirely computer generated.

I was challenged recently by a consultant colleague, who asked for 3D visualisation on a project on which we were both collaborating. My immediate thought process ran to the cost of the software that I expected that we would need – software that we didn’t have. It prompted me to explore a few of the things that have been floating at the bottom of my task list for some time. As well as wanting to explore in more detail the benefits of visual scripting with Dynamo and Revit, I wanted to undertake a comparison of Unity and Unreal Engine.

It’s fair to say that throughout my architectural career, I have been firmly in the Autodesk camp in terms of the software that I have used, but also publicly endorsed as a speaker at industry conferences on BIM (Building Information Modelling). Unity is integrated into the Autodesk AEC (architecture, engineering and construction) product workflows, which would make it an obvious first port of call.

I think in business, we should always be working towards something; even so, if we have an end-goal, being rigid in our approach to that focal point can mean that we miss opportunities to learn – to practice. One of the principles I apply to business, is trying to remain agile and adaptable. Inspiration to try new things – to explore - can come in many forms, but I remain most influenced by visual media.

With shared origins in 1977, Star Wars and the galaxy far, far away keeps finding ways to draw me back in - this time as analogous to my current line of exploration, in film, gaming and architecture, offering contemporary illustrations of each that are tied together by a common, relevant, technological thread.

More than a decade after starting my first architectural practice, in a recession, I’m now running my second architectural practice and guess what, circumstances are once again pressing businesses across the planet in sudden and severe ways.

The image of the Death Star chasm feels all too relevant; the metallic shaft before us represents the only way forward. With a perilously thin rope in hand, we still have a choice to make; do we try and hold our ground, knowing that the competition to hold our position will get even harder? Or do we attempt to swing across, believing that when we’re on the other side, our effort and determination will at least allow us to continue, marking us out as different to those that avoided the risk? It has to be better than what we have right here, right now, on this increasingly crowded ledge.

So, we take a breath, and swing over towards Unreal Part 2 : Film.

Star Wars: Episode IV - A New Hope (1977)